Does Beardtown exist?

Actually, this question unexpectedly elicits a secret shame I have lived with my adult entire life. Because of mixed genetics I have inherited from my-multi-ethnic-but-still-European-descended family, I lack the rather manly ability to grow a full, bushy beard. Viking, I am not. Nor will I ever be.

My dad suffers the same. An inside joke between us is: don’t shave for a month or more, and either of us may end up looking like the late Palestinian Liberation Organization leader Yassir Arafat. All that means is that there always ends up being empty, barren, and smooth patches on my neck and cheeks. In other areas, singular rogue hairs protrude and then spiral out of control. If you selectively pluck them with tweezers, they grow even more serpentine and longer. The most logical response is to just nuke your face and shave it all off with a mutli-bladed razor and an aloe-based foam. Dull-and-cheap single blades may hack up your face, produce scabs, and prompt your friends to ask if you’ve been hard drinking again and fell off your bike — when you haven’t in a very long time

Every time I have actually tried to grow a beard, the results have been disastrous. The most recent was during the initial onset of COVID-19 and its resulting lockdown in Changzhou back in 2020. I had the really dumb idea of “I shall not shave until there is a COVID vaccine!” Months went on and on. The more I gazed upon my reflection, I was just constantly reminded that I could not even grow a competent moustache, goatee, or soul patch.

Think about that; the bushy hipster triangle of follicles beneath a man’s lower lip that enrages most – I can’t even have that. I can’t even troll people with that. Maybe I should be grateful? Growing hair just because you can is a confirmed case of insecure and aging masculinity. Yet, in a man’s more desperate and impotent moments he might be willing to accept any sort of facial hair. Just because. I would equate the beard-deprived desire for just-a-soul patch as the same as bald men who does greasy comb-overs over a sunburnt scalp. The same goes for heavy metal gods experiencing male-pattern hair loss and compensate by growing out absurdly long beards. If they can no longer flair hair while head banging, at least they have reversed-compensated with a swishable beard, responsive to all head movements.

Just the term Beardtown elicits imagery of a desolate like Appalachian mountainside hamlet where all the men have crazy beards with a slight look of murder in their eyes look in their eyes. During my time in West Virginia back in the 1990s, it felt like that whenever my older brother and I got lost in the mountains once we left the interstate highways between Huntington and Morgantown — thinking we had found a solid back road shortcut.

At this point, it would be fair if somebody reading this might ask: what is even the point of this other than some loser blogger’s beardless pathos?

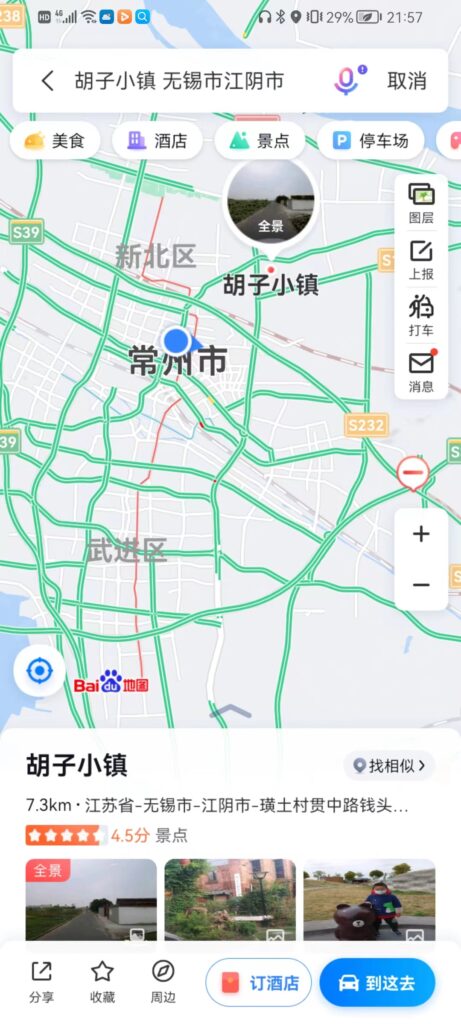

So, let me just rush to my point. Beardtown is not a product of my weird imagination. It’s a place that exists in the county-level of Jiangyin (Wuxi), and this would be the Huangtu part where you can actually see Xinbei landmarks like the media tower off in the distance. I have known of its existence for years, but I could never actually find it. I could only find signs pointing its direction.

So, I have spent years of wandering around this part of Huangtu obsessed with Beardtown and what could actually be there. Instead, I just saw a lot of stuff like this.

Or this.

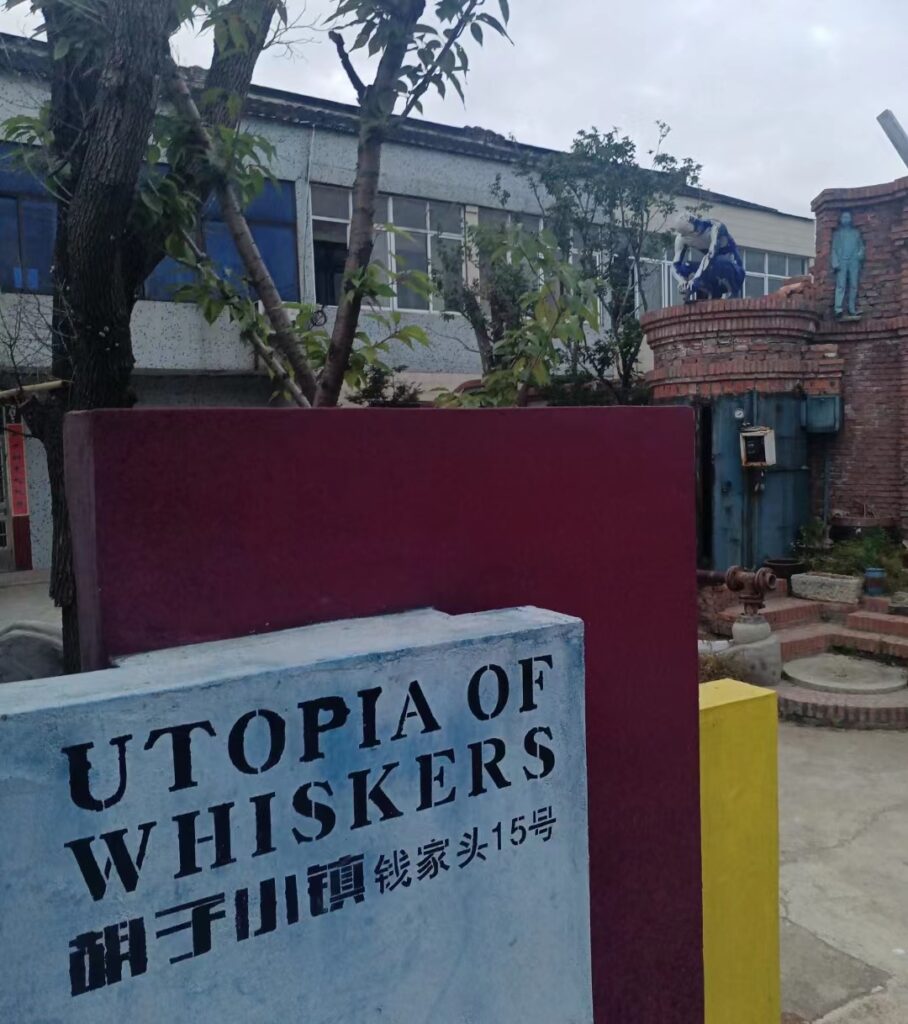

After all those years, I finally found Beardtown. It was easier than I thought. I actually paid attention to the Chinese characters of 胡子小镇 and not the English name. One quick map search later, and I realized that I had by walking past the place for years and not noticing.

Admittedly, the place was not what I expected. There were no scraggly facial hair anywhere! That being said, the place is still pretty surreal.

As it turns out, Beardtown is a tiny art campus affiliated with at least a Shanghai company and a Nanjing university. The surreality around this area is almost like a non-sequitur. For example, there is a golden-colored NFL statue between playpens for kids.

While Beardtown doesn’t actually feature anything with facial hair, there is one slogan that is painted all over the space.

It’s an intriguing slogan for a place called Beardtown. However….

There still not an actual follicle in sight. Just crazy art. I am not complaining. This small place is actually much more interesting than West Virginian hamlet with a bunch of dudes with stringy beards down to their knees.

There is a café here, though. This place is just so weird, but it’s also an interesting place to just sit and drink some coffee and soak in some ambiance.

Or tea and fruit.

It’s important to remember that Beardtown is just one tiny dot in a part of Huangtu that’s been zoned and urban planned for “rural tourism.” As far as I know, no busses actually come here. But, it’s an easy ride from Changzhou on an e-bike, car, or a DiDi — especially if a traveler is starting from Xinbei.

I just know, that over the years, this whole area, despite my “No Sleep Till Beardtown” obsession, has some weird things to look at. This, after coffee and cake, was spotted on the back to the car. At least this building has a moustache.

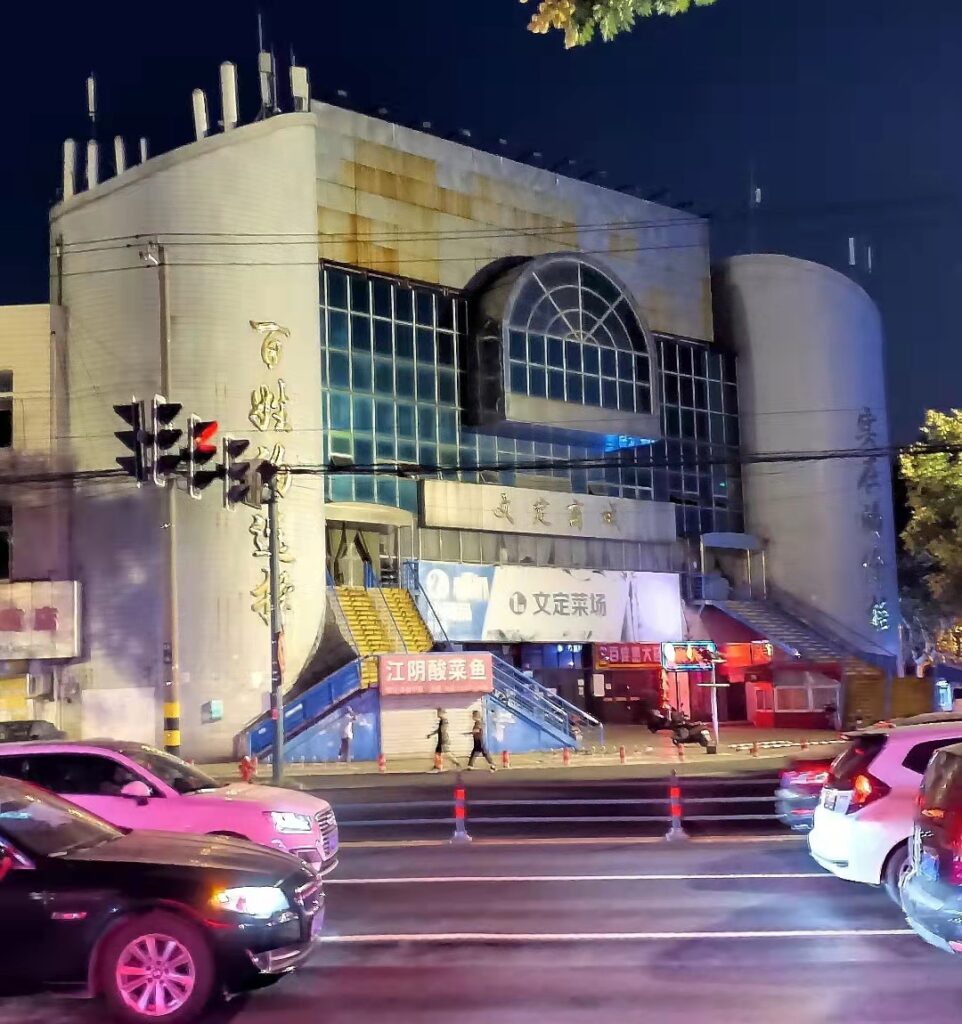

While visiting Jiangyin either on business or as a tourist, there are a few western restaurants to consider eating at. While the city is smaller than Changzhou and belongs to Wuxi, Jiangyin is highly developed and quite modernized. There is one spot in the downtown area that seems to be central to dining and nightlife. Yijian Road has a lot of bars and restaurants.

While visiting Jiangyin either on business or as a tourist, there are a few western restaurants to consider eating at. While the city is smaller than Changzhou and belongs to Wuxi, Jiangyin is highly developed and quite modernized. There is one spot in the downtown area that seems to be central to dining and nightlife. Yijian Road has a lot of bars and restaurants.