In the cultural history of Wuxi, Abing is a heavyweight. In many respects, he is remembered as a folk hero — here was this blind and impoverished Taoist priest roaming around Wuxi while writing and playing music on his erhu or pippa. Some of his songs were topical, and some of them are still transcendent. Not a lot of his creations were written down as sheet music, and only a few have been recorded for posterity. Imagine if somebody in America like Woody Guthrie had their body of work lost to history. Abing’s surviving compositions are now considered Chinese national and cultural treasures.

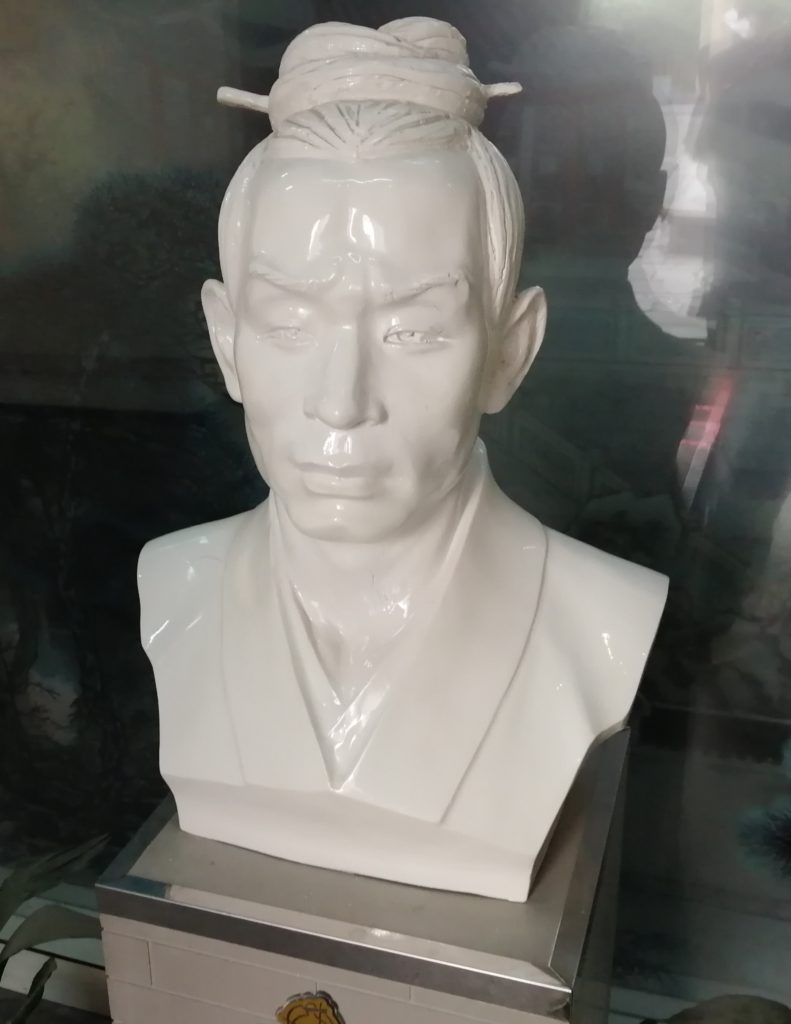

In Wuxi, his home has been preserved as a museum in his honor. Upon my last visit, I was struck by the sculptural and artistic renditions of him. Some are quite surreal. Here are some pictures to that end.

Let’s start with a fairly realistic head bust for comparative value. Now, let’s move on to a selection. The following are not all of the sculpture’s at Abing’s former home. It’s just a quick sampling.

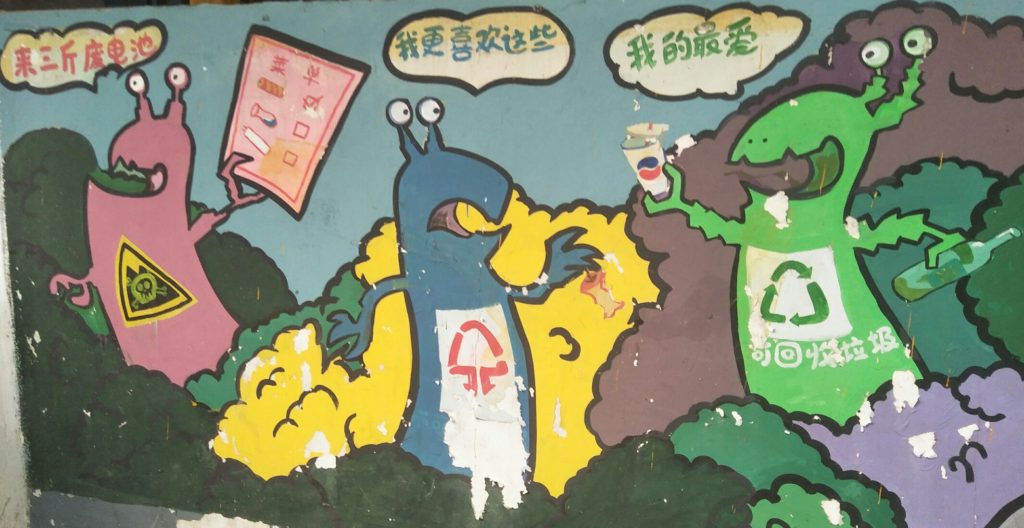

Most of the sculptures — and their dreamlike qualities — make Abing seem like a larger than life figure. But, then again, most folk heroes are just that: larger than life. And, the legend of a person may or may not gel exactly with who they actually were. Still, here was a Chinese musician who engaged the imaginations of his listeners. It’s only fitting that he have equally imaginative artistic renditions of his likeness.