Honey Trap (noun): A spy using seduction and sexual acts to compromise a target for purposes of blackmail. Example: A Russian hyper male FSB officer falls for a twink CIA dude while dancing at an illicit gay bar in Plovdiv, Bulgaria. Strobe lights and mirrored disco ball spinning from the ceiling are certainly involved as they make eye contact. Afterwards, the two relocate to a hotel room so they can be very naughty with each other. The Russian becomes a double agent as a result to keep his real sexual orientation secret from his FSB coworkers.

Honey traps are frequent plot points in James Bond movies and TV shows like The Americans — or just about any entertainment product involving espionage. However, there are more to them than just John Le Carré novels and stories like them,

Sure, a bit of sexy intrigue does spice up a fictional plot and narrative, but honey traps are actually a part of world history. During the Cold War, Warsaw Pact nations did this on a routine basis, where handsome young men were often dispatched to seduce secretaries within the Pentagon and within other American governmental agencies.

In a time of rampant and institutionalized homophobia, it was particularly effective if you could ensnare a closeted lesbian or gay man, because that person would be even more existentially compromised. The illicit secret might become very public. This is why, by the way, the previous joke above regarding gay discos in Plovdiv, Bulgaria, actually is quite real and not a total joke as it originally sounds. If the game is hard intelligence in a pre-Internet world, a spy doesn’t have to bring down a high ranking official. A spy just needs to seduce somebody who has access to a higher ranking official’s filing cabinet and documents.

If you go back farther into ancient history, a honey trap may not even involve access to papers. It might involv sending a beautiful woman into somebody else’s kingdom — just to create chaos. That actually was purported to have happened thousands of years ago in what is now Jiangsu and Zhejiang provinces. This was during the Spring and Autumn era (770-476 BCE), and the specific kingdoms were Wu 吴 and Yue 越. This should not be misconstrued to having anything to do with Wuyue shopping plazas; those characters are 吾悦. Anyhow, Wu was predominately modern Jiangsu, and Yue, Zhejiang. The border between the two sometimes shifted due to ongoing war.

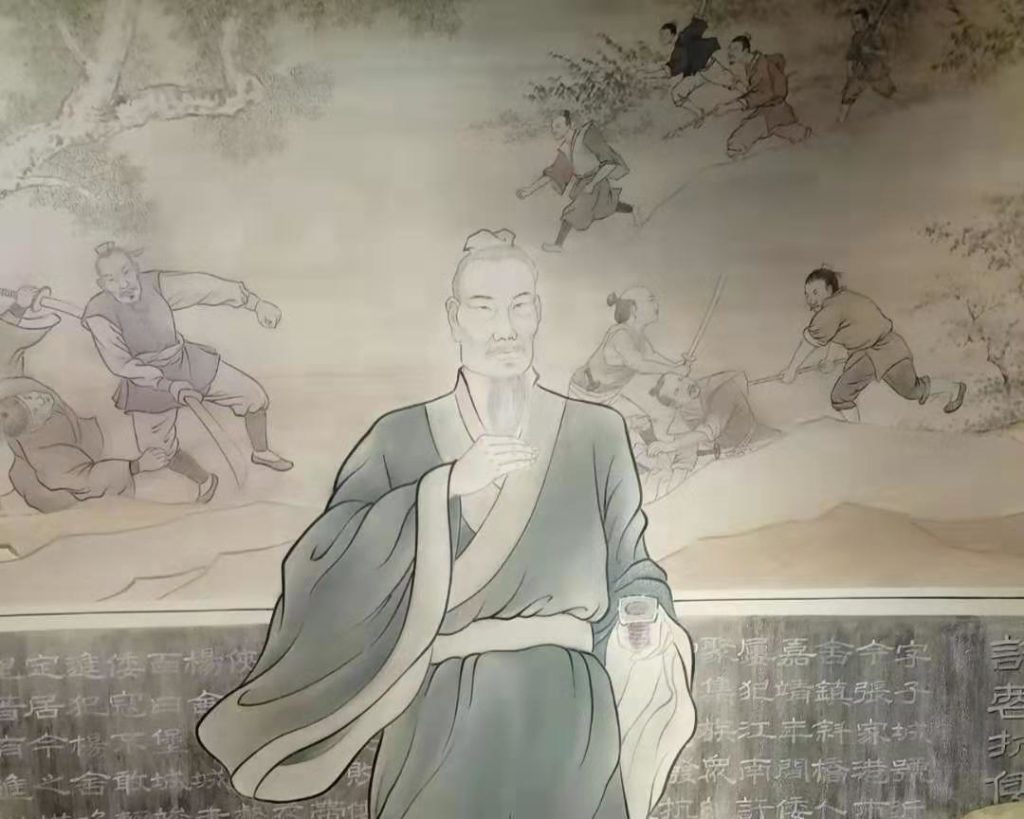

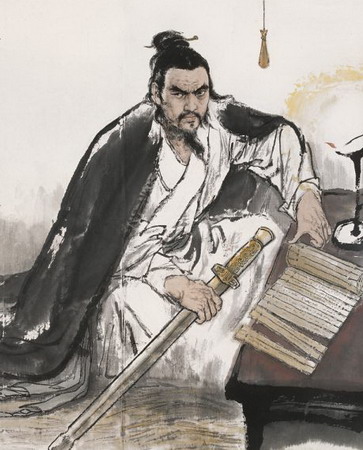

Gou Jian sat on the Yue throne from roughly 495 to 465 BCE in what would become present day Shaoxing (a city between Hangzhou and Ningbo). At the beginning of his reign, King Helu of Wu had his army march south and attack. Gou Jian defeated that advance and pushed the invaders back. Helu never forgot this, and on his deathbed, he commanded his son and heir, Fu Chai, to avenge the loss.

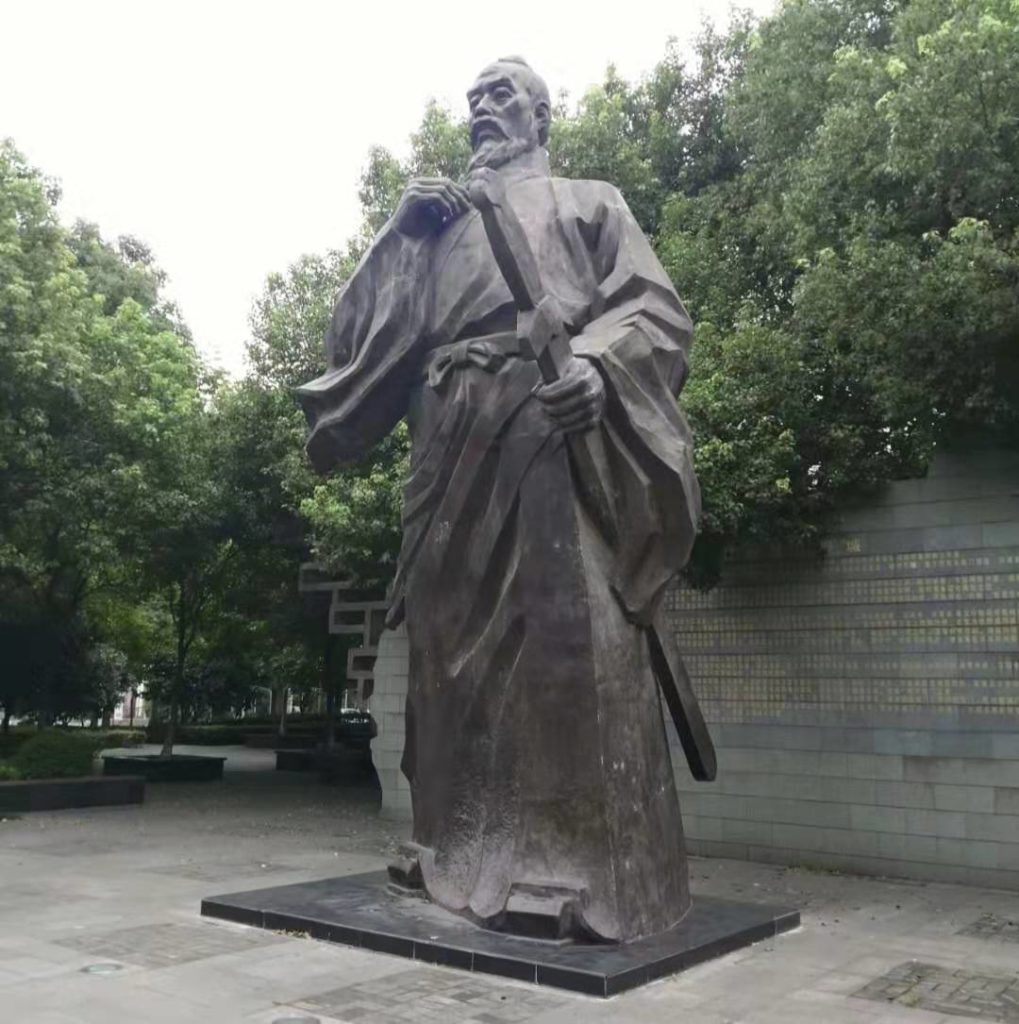

Eventually, he did, and he took both Gou Jian and his top advisor, Fan Li, prisoner. Both were forced to work as slaves performing manual labor. Guo kept his misery to himself, and after a few years, the Wu king granted the Guo and his advisor freedom and the ability to return to south to Yue. That was a colossally bad idea. Once returning to their own country, the two dedicated themselves to plotting the tragic downfall of Wu and Fu Chai. Of course, that involved troops, but Fan Li had spicy idea to plop on top of that.

As tribute from Yue, Fu Chai was gifted a beautiful woman, Xi Shi. She was so gorgeous, according to legend, birds would drop out of the sky if they caught a glimpse of her. Also, if fish saw her peering into their waters, they fell to the bottom of the river; they would become so mesmerized that they would forget how to swim. She is credited as the origin of the Chinese idiom 沉鱼落雁 chén yú luò yàn — literally “Fish sink and wild geese drop.” It’s often used to describe woman who are so beautiful, men literally go insane while looking at them.

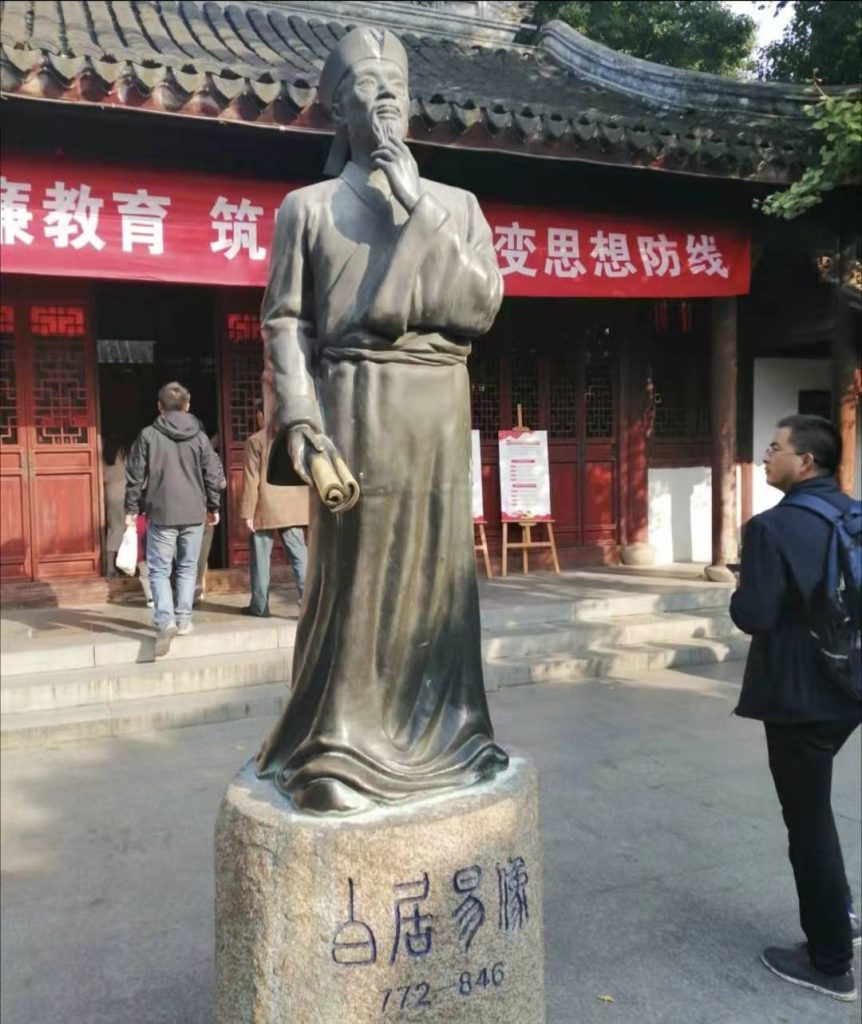

The idea, basically, entailed that Fu Chai was a fundamentally horny man who couldn’t control himself. If he had the stunning Xi Shi all to himself, his constant arousal would distract him from matters of state and the Wu kingdom would fall into disorganization. That’s exactly what happened. In the end, Guo Jian prevailed. While Yue forces sieged the Wu capital of Gusu (part of present day Suzhou) for the final time, Fu Chai committed suicide. Yue absorbed the Wu kingdom thereafter in 473 BCE.

One could easily argue that Fu Chai fell into one of the oldest honey traps in history. This is one of the epic Chinese stories that a person can easily find English YouTube videos on. That’s nice, but one can easily look at my clickbait-ish title and ask what Changzhou has to do with this. It’s where, allegedly, the story goes after the fall of Wu.

People who misunderstand this story might accuse Xi Shi of a sluttery; they might also accuse Fan Li and Gou Jian as being her pimps. This leaves out the fact that she was possibly a willing third accomplice, knew what she was getting into, and did it because of a sense of duty to her country. How different is this story from the one of KGB women spreading their legs to get kompromat on Americans or western Europeans? Every spy has a handler. And those managers have managers,

To that end, Xi Shi and Fan Li were also lovers, and she likely gave herself willingly to Fu Chai at Fan’s direction. The Yue King may have merely signed off on the plot. After Fu Chai killed himself and the Wu Kingdom became ripe for annexation, King Guo Jian of Yue deemed it necessary to purge (assassinate) many of his advisors and reboot his court with fresh faces. Fan Li anticipated this, and he and his eventual wife fled together.

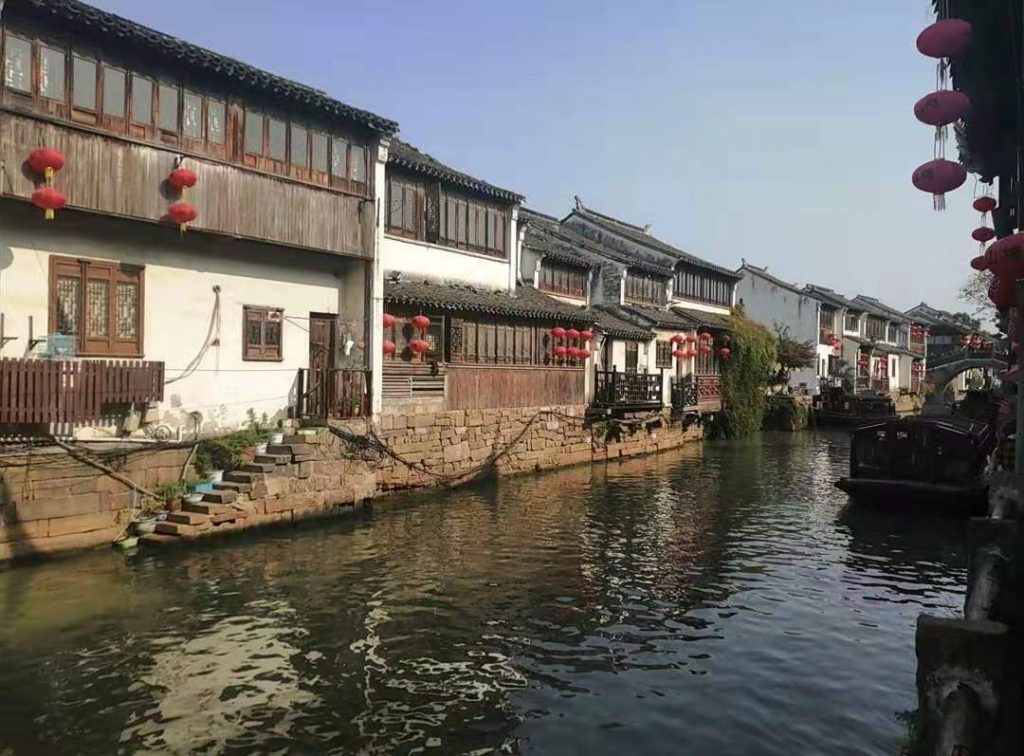

At the time, Changzhou was not known by that name. It was Piling 毗陵. Fan Li, during his time in town as a Yue governmental minister, also over saw the dredging of canals. One of which involved a waterway connecting Lake Ge (which everybody in Changzhou now calls Xitaihu) and Tai Lake — the third largest freshwater body of water in China. Canals in ancient China were a network of liquid roads. Something a lot quicker than riding horse or donkey out of town. A getaway car in this period of Chinese history is a canal boat, and Fan Li likely knew how to navigate that system.

Changzhou claims to be the departure point of Fan Li and Xi Shi. It is here they got away and evaded detection. At some point, Piling was under Yue control, and Fan was in the area overseeing the dredging of canals. There was a need to connect Lake Ge (what everybody know calls Xitaihu) with Tai Lake, which is the third largest freshwater body in China. It is argued that, with government agents in hot pursuit, Xi and Fan boarded a canal boat in Piling, navigated the system of artificial waterways to the vast safety of Tai Lake. Of course, with a story this old, there are other variations and it’s hard to confirm 100% accuracy.

There is a marker in present day Changzhou commemorating this story. It bares the name 西蠡古渡 xili gu du, or Xi Li Ancient Ferry. Of course, “Xili” is a name combination technique. These days, it’s used to name celebrity couples. For example, Ben Affleck + Jennifer Lopez = Bennifer. It would be silly to claim that this marker and the accompanying stone pavilion actually dates to antiquity. It was open to the public back in 2010.

It is a narrow strip of green space next to a canal. There are multiple boarding points and loading and unloading ramps for cargo.

Besides this, there are views of the canal itself.

This small bit of canal area is not that far the Wuyue 吾悦 Plaza downtown. Truth be told, the area can be seen in about five minutes, and what is there is not as epic as the story that inspired them. How could it be?