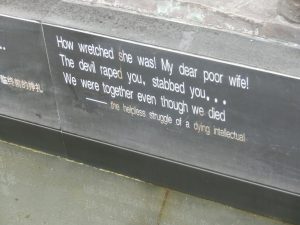

The first time I ever visit a city, I like to wander around without a plan. The idea is that the new location will reveal itself to me in its own time and manner. Sometimes that works, and sometimes it doesn’t. Recently, I decided to go to Zhangjiagang, because, well, I have been meaning to for two years now. I mean, it’s only a little over an hour by bus from Changzhou. Not that far from the city center, I ran into a a statue of what looked like an ancient statesman.

Public sculpture has always intrigued me — especially when it’s not abstract. It usually signifies and represents the history and the stories a city or a town wants to tell. Since the above photoed figure is holding a sword, it probably means he was some sort of heroic figure. Unfortunately for me, the Chinese text on the wall behind the statue didn’t read well on my phone.

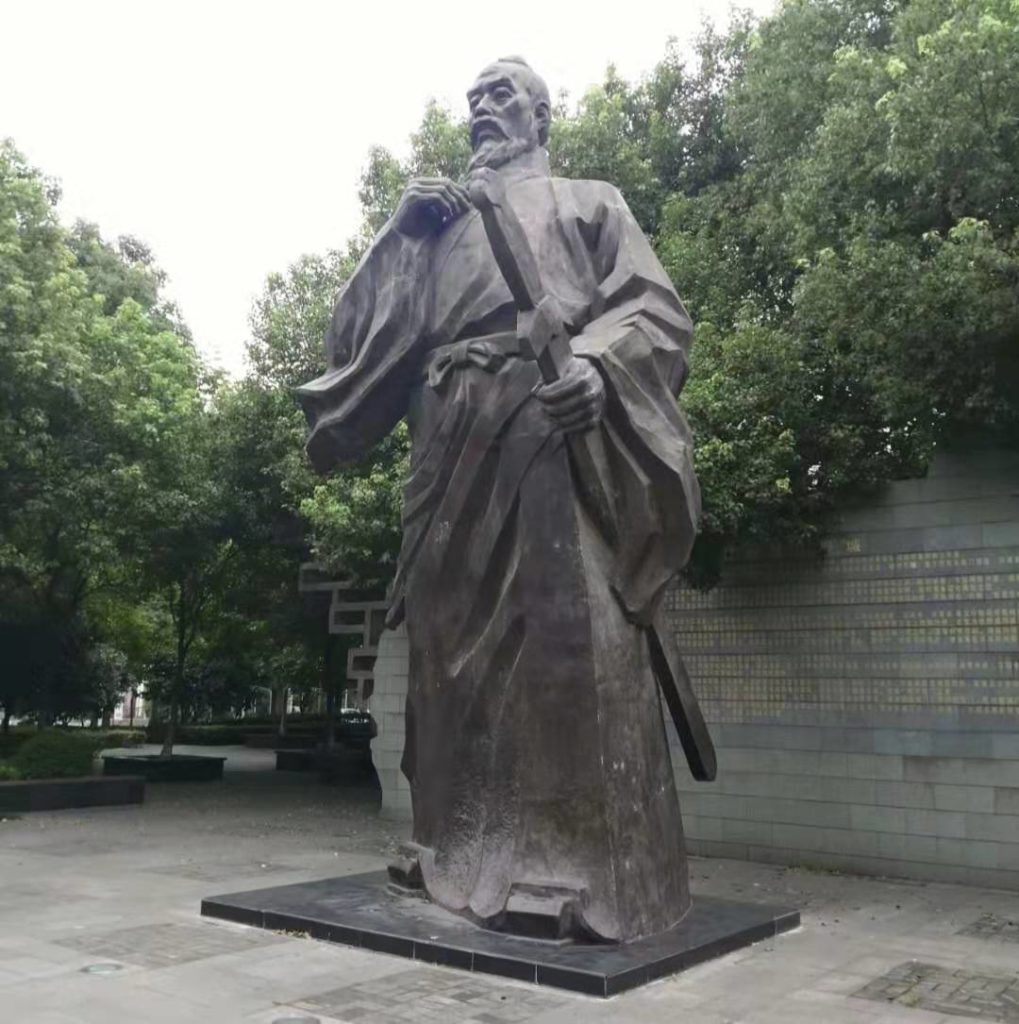

All I could really get was “许蓉抗倭…” And that translated as “Xu Rong fights Japanese.” In this case, 倭 is an archaic character for “Japanese.” It’s no longer used in everyday Chinese, so the ones he had to be fighting had to be really, really old. Thankfully, there was a bas relief sculpture on the other side of the wall. It depicted a very chaotic scene. Here are two details.

Further intrigued, a made a few more attempts at translating the explanatory text behind the Xu statue. All I could glean was another word: 倭寇. In English, that would be Wokou — with a spelling variant (from a different Romanization scheme) of “wako.” These were Japanese pirates. I left the statue and wandered around to see what else downtown Zhangjiagang had to offer. My thought was once I eventually returned to my hotel room, the Internet would help me fill in the rest of the story. Of course, it didn’t. I searched in both English and Chinese and turned up next to nothing on who Xu Rong was.

So, the next day, I went The Zhangjiagang Musuem. Surely, there had to be a mentions of the Xu there.

There was some mention of him, but not a lot. He lived from 1500 to 1570 — basically, during the Ming Dynasty. There were more mentions of Japanese pirates, but that was about it. Apparently, these Wokou attacked the town and sacked it several times.

The above obviously is from Pirates of the Caribbean, and it’s of Chow Yun Fat 周润发. It is also the highest profile representation of the Wokou in western culture. Because, the more I could not find information about Xu Rong and why he’s a hero, I was able to piece together a bigger picture.

The Wokou started off as Japanese pirates raiding and pillaging Korea and coastal China. But, Zhangjiagang is not a coastal town. However, it is near the Yangtze delta and the Wokou had no problem sailing up river and causing chaos inland. That being said, if these pirates were Japanese, why do you have a Chinese actor playing one? History is a little more complicated. So, let’s back up and talk about this dude.

This is the Jiajing Emperor — born as Zhu Houcong. Pretty much, he was an useless ruler and a terrible human being. He was an ardent Taoist and was into alchemy. He thought if he drank the menstrual blood of virgins, he could prolong his life and attain immortality. He actually kept a harem of young girls for this exact purpose, but he treated them so badly that his phalanx of concubines tried to assassinate him and failed. That was the Renyin Plot, and those concubines were slowly tortured to death for the efforts. Oh, and their family members were also beheaded. It’s pretty gory reading, as far as history goes.

However, that is beside the point. He, like other Ming Emperors, was an isolationist. Trade with the outside world had been made illegal. There were coastal communities that were basically not allowed to capitalize on their greatest local asset: proximity to the sea. So, eventually, a some Chinese people started joining the Wokou. There were even Portuguese sailors among their ranks. So, these pirates started off Japanese, but they were largely international during the Ming Dynasty according to some historians. So, having Chow Yun Fat play an Asian pirate may not be that far off from the truth.

However, let me digress back to Zhangjiagang. The years of the Jiajing Emperor were the worst when it came to Wokou incursions into China. According to Wikipedia, there were 602 pirate raids during Jiajing’s reign. At the time, China didn’t have much of a navy to defend itself because of Ming rulers thinking the world outside China was irrelevant. Some towns like Zhangjiagang had to turn to local officials like Xu Rong to try and address the issue.

So, who was Xu Rong? Truthfully, I still don’t have a clue. However, trying to figure that out did teach me some historical lessons I didn’t know before. That’s a good thing. Also, another takeaway from all of this is that some of the Chinese distrust of the of the Japanese goes back A LOT longer than World War 2, the occupation, and the war crimes that came with it. This is true if were are discussing Japanese pirates — however international their crews may have been — attacking a town like Zhangjiagang during the Ming Dynasty.