Steam technology came to China during the Qing Dynasty, and there is an interesting dynamic to think about there. In Ancient history, the Chinese were essentially global leaders of innovation. Gun powder, for example, came into being during the 9th century, and the Chinese followed that up with the “fire lance” a hundred or so years later. This was basically a tube at the end of a spear the could belch out fire and sometimes, if one had some really nasty intent, flaming hot shrapnel. The fire lance was the precursor to all firearms and guns to follow.

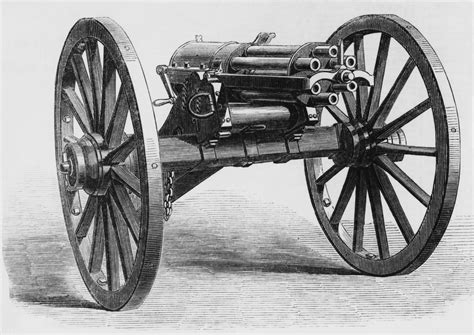

Ask yourself how something like that didn’t change the world? Then, somehow, China lost its edge. During the Ming and early Qing Dynasties, The Middle Kingdom shut itself off from the rest of the world. In isolation, the culture slowed its technological growth and the west caught up and surpassed China. Once the later Qing reopened to western trade, China had a lot of catching up to do. What good is a ancient Chinese fire lance in battle when Americans invented the first rapid-fire machine gun? (The Gatlin Gun)

Guns or otherwise, the Chinese had fallen behind. So, back to my original point. The British first demonstrated a steam powered locomotive to imperial court in 1864, and the trend from there indicates that most of the innovations like this came from foreign sources at high cost. Most people and nation states dream and aspire towards self reliance. So, you can imagine how some Chinese people would actively want to make their own steam engines and not have to pay top sums of money for a foreigner to manufacture one for them.

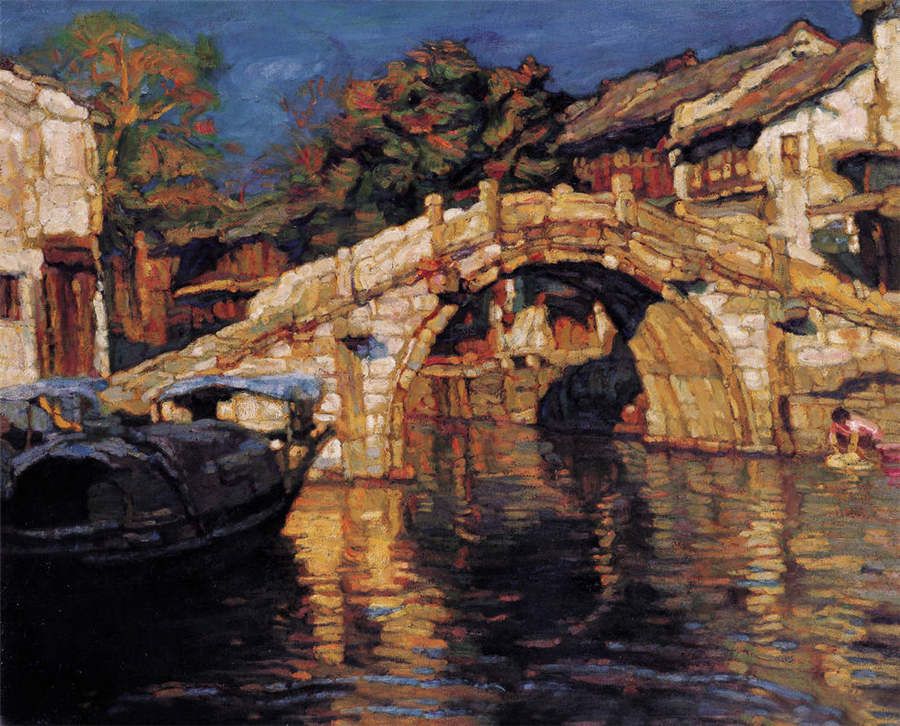

Here is where an interesting — but almost forgettable — little display in present day Wuxi comes into play. It’s along the Liangxi Touring Recreational Greenway. This is a part of the greater Grand Canal network of artificial waterways that can be found in cities from Hangzhou to Beijing. This particular stretch of water is walking distance from Wuxi’s central train station and is near a thick cluster of dance clubs.

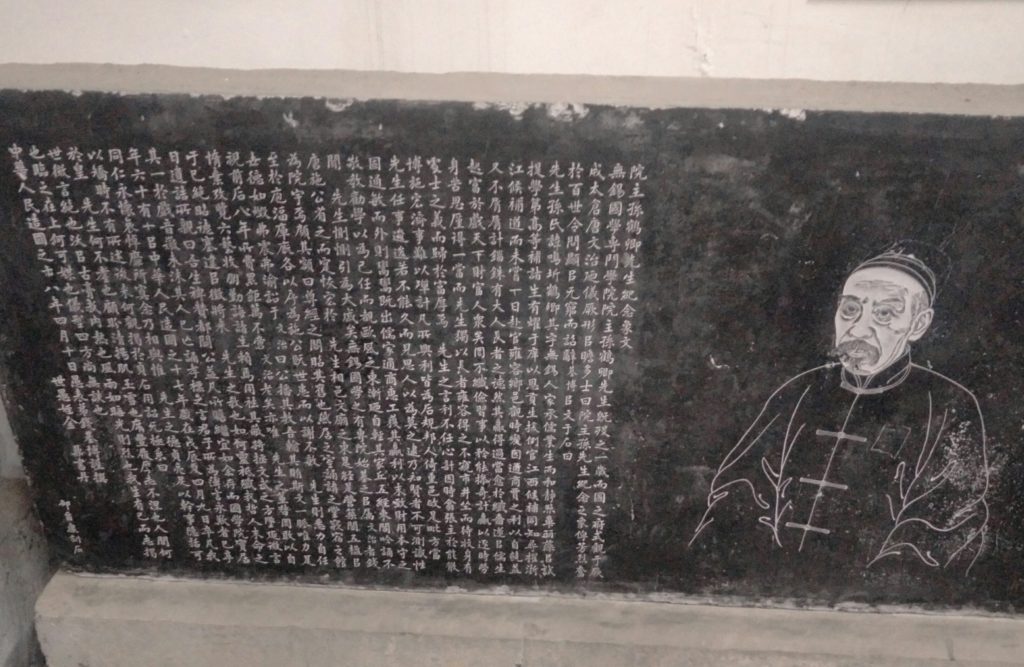

So, what exactly am I talking about? There is a replica of a steamship permanently moored to the side of the canal here. Next to this boat, three statues of Chinese men stand. In all likelihood, they are Xu Shou with his son, Xu Jiangyan, and a family friend, Hua Hengfang. These three conceived, designed, built, and test drove the first steam-powered boat ever locally produced in China. This endeavor was funded by Zeng Guofan. He is perhaps more well known for his efforts in helping to put down the the extremely bloody and destructive Taiping Rebellion. So, this little boat thing in Wuxi is more of a minor footnote on his career as an imperial official.

In some respects, China is still playing “catch up” with the west when it comes to technology. In other areas, like the building infrastructure like roads, rail systems, subway networks, and much more, China is already leading and has left the USA far, far behind. But, in history, a lot of things are interconnected in subtle ways. So, Wuxi’s claim to have been the home of the first domestically created steamship engine may not sound like a big deal. It may still sound like a footnote in history, but even footnotes have context and greater meanings.